Tuesday, December 29, 2009

9 Dragons, by Michael Connelly

Sunday, December 27, 2009

Dearly Devoted Dexter, by Jeff Lindsay

Thursday, December 24, 2009

Darkly Dreaming Dexter, by Jeff Lindsay

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

The Lost Art of Gratitude, by Alexander McCall Smith

Sunday, December 13, 2009

Pharmakon, by Dirk Wittenborn

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

When Will There Be Good News? by Kate Atkinson

What a pleasure! An interesting array of characters and plenty of action, but that is not all.

The central character is Joanne, who suffers a great loss when she is six. We get to pick up on her life thirty years later, where we find she has become a doctor, is married and has a baby son she adores - and may be threatened by the same man who destroyed her family 30 years before. Joanne is kind and thoughtful and just possibly stronger than she looks.

On another track is Louise, a police detective particularly obsessed by cases of violence against women. She too is married, to an understanding and unflappable doctor, but she feels the need to test their bond again and again. She is prickly and aggressive.

Jackson Brodie is a former detective (also former police detective and former military guy), newly married yet on a trip to see a young son whose mother insists is not Jackson's. By a stroke of luck, Brodie has inherited big bucks so does not have to work, but he does not feel he really earned it so does not flaunt it. Brodie was central in Case Histories and One Good Turn, Atkinson's previous two novels, as well. His trip is more adventurous - and dangerous -than he would like.

Primary driving force, though, is Reggie. Reggie is a sixteen-year-old girl ("with a boy's name") who takes care of Joanne's baby and dog when the doctor is at work. Having struggled through quite a life already, Reggie is remarkably open to affection and is tough and resilient. She is also loyal and determined. It is Reggie who really brings everyone together. Reggie is also quite the little scholar, learning primarily on her own. Atkinson nails the teenage speech, which I found highly entertaining.

Joanne disappears one day and Reggie seems to be the only one who thinks there is something suspicious about the story her husband offers. The baby is with her but not the dog. And not a few other things that Reggie in particular insists would have been with her.

Beyond the suspense of the story there are the characters. All fully-formed persons, we get to see how they make decisions, good and bad, and act intelligently or not. We also get a great sense of place and custom, without being overwhelmed by it. The book is enjoyable for its quiet humor and believable characters, beautifully drawn, so fun to watch.

Friday, September 25, 2009

American Wife, by Curtis Sittenfeld

I read voraciously, yet it is rare for me to enjoy a book so thoroughly as I enjoyed this one (this blog does not contain reviews of all the books I read; only the ones I consider notable for some reason).

Sittenfeld, after reading a biography of Laura Bush, realized that the former first lady is a complicated person, an interesting person. Her life seems like a novel. So she decided to write it. Yes, it’s fiction, but many of the basic elements of Laura Bush’s life are also in the life of the fictional Alice Lindgren of Wisconsin. By creating this character Sittenfeld has license to explore Alice’s thoughts, her emotions, her character, to bring her alive yet acknowledge, in the end, that she does not really exist.

The parallels are so close as to suggest that Sittenfeld is sorting through events in the Bushes’ lives and trying to create character from the bits and pieces she knows of the individuals. It would be presumptuous to write a biography, inserting the answers, the whys throughout, without even meeting the subjects. But the whys are what are so interesting. Who is Laura Bush and why did she behave as she did in the Bush White house? What caused her to marry George W. Bush?

More than a story of the presidential years, though, this is an investigation into love, and, delightful to me personally, a close look at what it means to grow up in the upper Midwest in the middle of the 20th century. I was born the same year Alice was and I was born in the midwest - Upper Michigan instead of Wisconsin. So much of what Alice experiences, how she reacts, how she feels, reflects how I have felt and experienced life myself much of the time. I think Sittenfeld nailed it, at least what it is like to be a bookish intelligent midwesterner with an open mind. Thus even though we are not alike I was able to understand how she acted, how she felt. Her life makes sense, her actions make sense.

There is much insight in here, in the ways our upbringings might cause us to see others very differently. For example, Alice acknowledges her own deep feelings and sense of obligation towards those in need, yet she can understand and accept that those raised in a privileged household, where they are kept effectively insulated from others, might not have the capacity to care in the same way. She does not blame them, but rather asserts her right to feel differently.

Another interesting insight is in her sense of obligation in relation to her position in the world. She finds herself occupying a position of influence - wife of the president - and realizes that with such privilege comes a greater burden: how much should she do to right injustices, to relieve suffering? How much can she do? What is her responsibility?

The novel offers an answer to the question, how can you love somebody with whom you so often disagree? Sometimes love has nothing to do with agreement; love may not be magic but its elements in this case may be reasonably defined. Alice’s quiet, thoughtful character is in stark contrast to that of Charlie Blackwell, the stand-in for George W. Bush. She is drawn to his essential acceptance of his own flaws - what you see is what you get. And to the fun he represents, that she craves. The story also explains how others might be drawn similarly to a candidate who speaks as plainly as they do.

The development of Charlie’s character is fully as interesting as Alice’s. We see how he comes to value loyalty over truth; how he can see disagreement as almost traitorous. We see how the clannish nature of his family provides a cushion against the world, and a history to live up to, a competition to join. We see, too, how being part of an Ivy League school extends that family, adds some sort of validity to a certain way of thinking.

One recurrent theme comes from mention of the children’s novel The Giving Tree. It is Alice’s favorite children’s book and she reads it in many places to many children. The story of The Giving Tree is of a little boy and a tree. The tree provides everything it can for the boy for his whole life and at the end provides a place to rest and is happy to do it. Did Alice represent the Giving Tree? Did she gladly give of herself to the man that she loved?

It’s a beautifully-written novel with complex, believable and sympathetic characters. Even without the parallels to recent history it stands tall.

Thursday, August 6, 2009

House of Sand and Fog, by Andre Dubus III

Oh, the choices we make!

Oh, the choices we make!A story of a house that isn't really about the house, but instead about three people from different worlds, all flawed in serious ways. The three become bound together the day one of them, Deputy Sheriff Lester Burdon, shows up at the house of Kathy Nicolo, another of the three, to tell her that her house is going to be auctioned off by the county to pay a bill that, in fact, Kathy never owed.

Colonel Behrani, an Iranian immigrant, now a naturalized citizen, reads of the auction in the paper and sees a way to support his family at last, by buying the house and later selling it for much more. Behrani comes from the elite class in Iran, but barely escaped with his life and family when the corrupt leadership of the country (supported by U.S. arms) was overthrown. He carries with him a sense of entitlement and resentment, even as he also regrets his association with the murderers in that regime.

Burdon has a weight to carry as well. Always the victim of bullies in school, he is finally able to get some of his self-respect back (perhaps that is how he sees it) in his present position. At times deeply-seated anger arises, however. He knows not to make his job personal, yet he does, time and again, taking advantage of the opportunity to stick it to the perps who upset him the most.

Kathy is just getting over her husband's desertion. Worn thin by repeated reminders from her family that she just keeps screwing up, she fails to tell them of this latest event.

So Kathy is kicked out of her house suddenly. She has nowhere to go and little money with which to support herself. She connects with the sometimes-volatile Lester and she becomes increasingly angrier with Behrani and his family, taking her resentment out on this apparently rich family who now live in her house.

It's a setup for disaster, frankly, yet early on I suspected there might be a kind of redemption, a growing understanding of each other's ways, a final, good ending. I felt manipulated when I saw this coming. It seemed too easy. I was wrong to see it that way, though. The story takes some zigs and zags that I never saw coming, all the way to the end. It's the kind of story I had to keep reading, even when, at times, it made my stomach hurt.

Falling, by Christopher Pike

Some might call it a "wild ride", for that it certainly is. But that description leaves out interesting details.

This is a tale where even the good guys can't be trusted. We don't know until the end if they will do the right thing or be caught up in their obsessions. For obsession is the name of the game here. Obsession, love, betrayal. One instance after another of betrayal and prevarication.

Matt Connor loves Amy. When she finally rejects him and marries another, Matt's feelings of love and hate merge into an obsession. He wants to get her back - and he wants to get her back. He wants her to hurt as much as he does. He devises a complex, devious plan that has to make you wonder, what kind of guy is he anyway? A good man turned obsessive by a bad woman? Or something else?

Kelly Fienman (her last name is misspelled on the book jacket) is an FBI agent who is also obsessive. She wants to be the one to track down and capture the bad guys. She goes off the reservation. Not once, but again and again. She is hurt badly in an altercation with a criminal, a serial killer who uses acid to kill his victims. IT is a hurt that could have been avoided if she had followed FBI procedures. In the doing, she creates a rift with her husband Tony, and finally Tony asks for a divorce. She feels betrayed and hurt. To what lengths will this hurt take her?

Jerk by dizzy jerk, we are on a carnival ride that threatens to go bad. I rooted for Kelly, but at the same time was disturbed by her ego-driven quests for fame and recognition. I am not a fan of vigilante justice, and I certainly was not a fan of her actions. I didn't so much root for Matt. Even though he seemed fundamentally a good guy his obsessiveness was deeply disturbing. The book is disturbing, clear to the end.

Sunday, July 12, 2009

Running with Scissors, by Augusten Burroughs

I really enjoyed this book. It's a family biography with a sharp edge, tempered by humor.

I read Burroughs' "real" memoir, The Wolf at the Table, before reading this one. The Wolf concerns itself with the early years, the years Augusten spent with both parents, and most particularly with his father. We soon come to realize how cruel his father was. There are episodes in that story that made my flesh crawl.

In this book, by contrast, Augusten is living with his mother as well as with the family of his mother's psychiatrist, Dr. Finch (the names are changed with good reason). He never sees his father, though he mentions him a couple of times in passing. Augusten passes from age 12 to adulthood here, and the book takes a much lighter approach.

Augusten thanks his parents, by the way, for giving him such a memorable childhood, however inadvertently. That childhood certainly was off the charts in strangeness, but I think the reason he remembers it so vividly is that he wrote about it all the time, in his journals. When I think of recording events from my own childhood I draw a lot of blanks.

But back to the book. Augusten's mother is a self-centered poet who is concerned mostly with overcoming what she considers oppression in her life. And just about anything, including a critical comment by her son, counts as oppression. She has a tendency to go off the deep end from time to time. Her son has an unerring sense of when these periods of madness are about to arrive. Thus Augusten eventually finds himself, from time to time, in the home of her doctor. And that life is no less crazy.

No calm, sensible guiding family there. Instead, Dr. Finch believes that when one reaches the age of 13 one has the freedom to do whatever. Further, he believes that most insanity comes from repressing anger. Thus the house is in constant chaos and the family members revel in acting out. At first this exposure is unnerving to the ultra-tidy Augusten, but in time he goes with the flow. And enjoys it, for the most part. Even takes part.

In a way, the book is about Augusten growing up in a crazy world but not being actually crazy himself. He takes on the observer role as much as the participant, and his observations are funny. At times, the events are very funny too, while at other times they hint at madness and horror.

While overall a very funny book, Running with Scissors also hints at the underlying pain in a boy growing up without a caring parent or substitute parent. He learns to take caring where he can get it.

Tuesday, June 30, 2009

The Brass Verdict, by Michael Connelly

The "Lincoln Lawyer" returns. After a year's hiatus, during which time defense attorney Mickey Haller goes through rehab and stays straight, Haller is abruptly thrown back into the world of law when a fellow attorney is murdered. Haller takes over most of the cases, including the "franchise": a prominent film producer accused of murdering his wife and her lover.

In addition to having to get up to speed quickly, to sort out what is going on in each of the cases, Haller is concerned that his own life may be threatened. In part for this reason and in part because the murdered attorney had been his friend, Haller begrudgingly lets LAPD detective Harry Bosch in. Haller wants the murderer caught as much as Bosch does, but is limited by law in what he can do to help Bosch. Their alliance is an uneasy one but one that seems to develop into almost a mutual respect.

As is the case with other Connelly novels, this one is replete with the details, is exacting in getting them right. Thus we can step right into Haller's shoes and feel the pressure as he takes steps to reconstruct a calendar, to track down clients. We also can breathe with him as he resumes his habit of working out of his Lincoln Town cars (three of them, rotated), watching the Suitcase City pass by as he is driven from one appointment to another.

It was a pleasure to read a Mickey Haller novel in which Bosch figures so prominently. It gives us a different perspective on the sometimes-explosive man-on-a-mission. It was also a pleasure to get to know Haller better, to follow his efforts to get back into the real world and perhaps to take steps to win his ex-wife back.

Away, by Amy Bloom

An extraordinary book. Small and simply written, this tale of Lilian Leyb is also poetic, beautiful, and full of characters we can believe in even as we laugh at their unexpected actions. Most of all, the character of Lillian is solid, strong, far from perfect yet yes, perfect.

Lillian finds herself in Manhattan with nothing but an address pinned to her coat. She speaks no English but does speak Russian and Yiddish and lands in New York in 1924, during the period when to be a seamstress means you can live. She has already been through hell in Russia, losing her family to horrific violence. Perhaps the lessons of that time are part of what keeps her going, adjusting to turns of events and accepting what she must accept, yet single-mindedly doing what she herself knows she must do.

Eventually Lillian sets out to return to Russia to find her little daughter, and her route takes her across the country and up through Canada and beyond. On this "road trip" unlike any other road trip she meets many people, as important as those she left behind in Russia and New York. Each time Lillian sets off again we learn the future, sketched lovingly, of each of these friends, a bonus that usually made me smile.

The details of Lillian's life in New York, her trip across country, her walk into the Yukon, are alive with a sense of reality. We can walk in her shoes even though for us it doesn't hurt.

Wednesday, June 24, 2009

My Lobotomy: A Memoir, by Howard Dully and Charles Fleming

I expected to like this book. I have done a great deal of reading about mental illness and the horrors that pass as cures, including lobotomy. Seeing lobotomy from the patient’s perspective is a rarity.

The story is certainly compelling. The telling of it is not. I suspect that a combination of the natural talents of Howard Dully and his co-writer, along with the effects of the lobotomy, is why the book is not all it could be. The book is unnecessarily repetitious, which takes away a lot of its power. Much of it is also infused with an adolescent point of view. I had the disturbing feeling that Howard Dully is a 50-something teenager. Or perhaps now a young adult.

I have heard that alcoholics tend to be stuck chronologically where they first became alcoholics. So if they were teens, that’s where they stay until such time as they burst free of the addiction, insofar as one can. It seems to me that the same might be said for this particular lobotomy. It was performed on Howard as a 12-year-old and his thoughts and actions for years afterwards mirror the feelings and impressions of a 12-year-old.

I became impatient with the explanations. Howard, as a young teen in Agnews, the mental hospital, did not know when he would get out. His reaction, therefore, was to “have fun”. Because he did not know nor was he able to control his future, he felt his only option was to have fun. This attitude, along with the lack of any real training for the real world, is what got him into trouble year after year. It also was the reason I had trouble liking Howard as I listened to this CD version of the book.

He recognizes, late in the book, that it was the lack of preparation for work or life outside that got him in trouble so often. Is this a common experience for people in similar situations? Those who are young and placed in mental institutions for a relatively short time? It seems an astounding lack of foresight on the part of the caretakers. How can you expect somebody to do well on the outside without the necessary skills? Even in prison inmates get an opportunity to train for some work.

The part of the book that is especially disturbing is the treatment of Howard by his stepmother Lou. The unfortunate combination of a distant father (emotionally), who does not share significant information or thoughts with his son, and a distrusting, disapproving stepmother who singled Howard out, was bound to have a significant effect on Howard’s behavior as a young child. He was beaten daily by either or both parents, he was not told of his real mother’s death when it happened (she just “left”), and it seemed to make no difference what he did. It makes sense that he acted out, that he rebelled, he made good on what his parents accused him of. When Lou took it upon herself to press for the lobotomy, Howard had nobody in his corner.

As I listened to the CDs I was also affected by the manner in which the book was read. It is not read by Howard, but by a skilled reader, who reads an attitude into the words. I was not fond of the way he read it and wondered if I would feel differently about the book if I had read the paper version. Therefore, I sought out information online, and especially looked for the NPR program featuring Howard. It was easy to find: NPR program

In this radio program we get to hear Howard narrate and talk to lobotomy experts and others affected by lobotomy. We get to hear the real Howard speak. His voice has almost a monotone quality to it, which is something I might expect of a person who has undergone a lobotomy. When he is emotionally caught up we can tell by the hesitation and difficulty speaking, so his delivery is not actually “flat”. I wonder if I would have liked the book better if it had been actually read by Howard. I think it’s possible, because it would have felt more real.

I am glad I had the opportunity to listen to this book, which I had not even heard of before I saw it on the list of books in a virtual book box through bookcrossing. It gave me a lot to think about. I do wish it had been more skillfully written, yet it is hard to see how it could have been done without changing the character of Howard Dully.

Saturday, June 6, 2009

So Brave, Young, and Handsome, by Lief Enger

This book became almost like an old friend to me. The chapters are short, so I could grab and gulp one down quickly in odd moments, and set it aside, feeling a sense of accomplishment. At the same time, of course, by picking up and letting down I didn't fully become engaged with the characters early. Or maybe it's just that kind of book: easy to read yet easy to set aside.

At least at first. The characters are intriguing, yet were difficult for me to get to know, especially the narrator, Monte Becket.

The story takes place around the turn of the century, in the early 1900s. Becket wrote an adventure novel that quickly became a best-seller, in spite of his lack of knowledge of the subject matter. He didn't know horses or adventure, yet his novel was about a western hero who triumphs over difficult odds by knowing how to ride, how to track, how to make love. The pulp fiction of the day.

Monte lives in Minnesota with his beautiful artist wife and observant young son. After the success of his novel he quits his job at the post office and tries to make a living at writing, yet he can no longer seem to find the words. Thus, he is feeling like a failure when a neighbor, Glendon Dobie, suggests he join him on a trip to Mexico to find the wife he left behind decades before. The neighbor is a bit of an unknown, but has found a way into the hearts of Monte's family, so Monte's wife urges him to go.

And thus begins an adventure for real. The trip doesn't go as planned in almost every way. Monte finds himself in situations that might have made good novel fodder if he'd been so inclined to use it. He is also challenged to find out more about himself, as so often happens in road stories.

I did not particularly like Monte until nearly the middle of the book. I didn't get a good feel for him, it seemed I couldn't grasp his essence, and what I did grasp I didn't particularly like. Yet by that time, the middle of the book, he began to change, or he began to assert those qualities of his that perhaps his wife knew and he had forgotten. From there on his decisions seem to be more outward - for the benefit of others - than internal.

Through much of the book, Monte and Glendon are pitted against a former Pinkerton's detective, bounty hunter Charles Siringo. As the novel progresses, Siringo assumes more and more presence and becomes almost a super-human adversary, seemingly evil to the core, yet...not?

Interesting, complex characters. A road show that almost assumes epic proportions. A story of a kind of redemption, finally, for more than one character.

Sunday, May 24, 2009

The Private Patient, by P.D. James: audio version

There is always something different about listening to a book as opposed to reading it. I enjoy listening to audio books as I drive around town and especially when I am on a long trip, but the experience is very different from reading one at my leisure, when I can ruminate over a passage or reread a section easily.

I admit that I did not hear - or absorb - every word on this CD set. Certainly I didn't skip any parts, but at times my mind went elsewhere while driving and I missed a bit here or there. Not much, I suspect, but perhaps some sentences that were important.

As is typical with P.D. James' novels featuring Adam Dalgliesh of Scotland Yard, this one starts with the characters central to the plot, in particular with the murder victim herself. And we know right off that she is the one. Rhoda Gradwyn, an investigative reporter in her mid-forties, meets with a plastic surgeon, George Chandler-Powell, to have him remove a scar that has been on her face since childhood. She chooses to have the work done at a manor house that has been converted to a part-time clinic. The surgeon divides his time between London and Cheverell Manor, keeping the manor available for very private - and generally very rich - clients.

When she meets with Chandler-Powell she tells him only that she wants the scar removed because she "no longer has need of it". Chandler-Powell is struck by the explanation but does not ask further questions. Throughout the book I looked for the reason but was never satisfied that I'd got it. I may have missed a connection somewhere.

Subsequent to a lengthy description of Gradwyn's preliminary stay at the manor (to get the feel of it) and her activities leading up to the day of the surgery, as well as a venture into her childhood, we meet the employees at Cheverell Manor, one or two at a time, find out how they came to be there and what their feelings are at the time.

Thus we don't get to the main action until disk 4 (out of 12).

It is rather satisfying to meet the characters this way rather than after the murder. We get a better sense of them and can follow them as they react to the murder and can consider who might have done the deed. We also get to see them through the eyes of Commander Adam Dalgliesh (A.D. to Kate, his subordinate), a quicker scan of how they appear then.

As well as we did get to know Rhoda I felt much was left out. She was private in more than one sense and as Dalgliesh considered later in the book, perhaps it is arrogant to hope to understand the motives of others. We do know she met with a young gentleman friend, Robin, who is excited about her visit to the manor and who mentions that he is a cousin of the assistant surgeon. He wants to visit Rhoda while she is there but she is emphatic that she will not welcome any visitors. I get the sense that she accepts Robin as an occasional dinner partner but is not interested in his ventures nor in becoming better friends. I sense she doesn't have close friends although she does have admirers.

A.D., Kate, and Benton, from Scotland Yard, arrive soon after the murder is discovered. They have been called in because somebody at the manor has connections and wants the best. They set off to interview everyone in the manor, to investigate the mysterious nighttime comings and goings of somebody, and down the line to follow up on other leads.

As is typical of old-style English mysteries, the only realistic suspects are the small group living at or on the grounds of the manor. James' mysteries differ from the old style, however, in the development of the characters of the main investigators, in the changes that enter their lives. It is perhaps better to read these novels in sequence, whereas with Agatha Christie, for example, it does not matter.

A.D. is looking forward to his marriage with Emma. At the same time, Kate manages to maintain an attraction to him and perhaps a better understanding of the whole man, but she knows the attraction is not returned. Unlike characters in other novels I have read, Kate does not pine and agonize and try to get A.D. to fall for her. She knows where she stands and she accepts it.

After the various twists and turns have resolved, in a sense, and the case is solved, once again we get a glimpse of the different characters and where they have gone, how their lives have changed. A rather neat wrap.

book rating: ![]()

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Outliers, by Malcolm Gladwell

Malcolm Gladwell loves studies and statistics. He hunts down the lesser-known and bends them to his will - in a good way!

In this book, Gladwell takes on the myth of the self-made man (or woman). He treks down various roads: the roads of birth dates, birth years, cultural backgrounds, and especially the road of opportunities. He finds connections between these elements and the potential for success in different fields. He shows how in hockey and several other sports, the month of birth is critical to the person's access to special opportunities that can lead to success. He follows airline pilots in different countries and shows how the cultural background of each can affect the number of accidents involving the pilots.

He takes us to the life of 13-year-old Bill Gates and shows how Gates was uniquely positioned to reach the pinnacle of power he now has.

In essence, he shows us how individual success is actually the success of a community, of circumstance, of the luck of birth far more than it is of a person simply working hard - but notes that working hard is always at the heart of it nevertheless.

What's more important is that when we understand these elements we can effect changes so that these opportunities are available to a greater number of persons. We might even find hints here for the raising of our children.

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Remainder, by Tom McCarthy

A young man - I do not recall ever learning his name - is involved in a strange accident and comes out of it not quite whole. He has all his limbs but he isn't able to use them as fluidly as in the past. Like a person with cerebral palsy (or, I suspect, other brain injuries), he has to learn to tell his muscles to take certain actions. He starts by imagining eating a carrot, learning every tiny step of the process of choosing, lifting, and finally eating the carrot. Then he learns to walk again.

Our character has friends but seems distant from them, not connected. He starts to notice that he is aware of himself, perhaps super-aware, of every move he makes. The injury presumably brought about this condition. At first he thinks he is alone with the condition but then observes others and concludes that just about everyone is somehow "acting" as they go about life. He yearns for the fluidity of natural movement, unconscious connection to the world.

While I found I did not particularly like the main character I could relate to his feelings in this sense. I have always been aware of myself, of watching myself, even down to a sense of how my lips feel when I move them, and certainly I can't stop myself from noticing how I react to others. For me this "observer" gets in the way of my being "real" and I am always second-guessing my actions. I have used unusual methods to counteract it, ways to release myself from that observer. So I understand how much this character wants to get past his.

His way of doing it puts this book into an entirely different realm.

Our fellow takes to "re-enactments". He has received a substantial settlement for his injuries so he has the money to do whatever takes his fancy. It begins when he wants to re-create an apartment building that he vaguely remembers. Did the building ever exist? We never find that out. We only know he feels he was "authentic" when he lived there and he seeks to find that authenticity by duplicating the entire building and surroundings.

He finds help and it really becomes, in a way, a two-person pursuit, with a staff of hundreds.

Yet for all that he doesn't pursue any real relationships with others. And his regard for others, while often generous, is also fleeting.

It's a book that is hard to put down. McCarthy has unleashed those dark and funny dreams here.

Monday, March 16, 2009

Nobody's Fool, by Richard Russo

I dipped in and out of this book for months. In between those dips i finished whole books, gulped them like milkshakes, enjoying the quick read. This book deserves more than a quick read. More, it's the kind of book I almost live in for a while.

The star of this show is Sully - Don Sullivan - a 60-year-old man who somehow lets "stupid streaks" take over. He isn't by any means stupid. He hasn't had much education but he has a quick intelligence that allows him to grasp a situation easily. More, he can see when he is heading downhill, can even say to himself, "stop now!" and will be helpless to stop himself. Once he has started an action nothing stops him.

He has a gift. One person, well into the book, says he is able to make others feel good. He does this by joking, by connecting with others through his often-sarcastic - but not mean-spirited - comments. Some people don't care for his way of being, because he has other personality traits that can drive one to drink. He forgets important things, like his son. He screws up jobs. He acts before he thinks.

All of this does nothing to give much of an idea of who Sully is. Only reading the book will do that. To me, a condensed description is that Sully is a man ruled in large part by his resentment of his father, now dead. He is unwilling to forgive the SOB, particularly because he saw that his father never asked for forgiveness. Never even acknowledged the pain and grief that he caused others. In this Sully is not like his father. His quick temper, unfortunately, mirrors his father's, reminding him that "the apple doesn't fall far from the tree".

While Sully is the star, the surrounding cast is well worth knowing as well. There are few authors who can create characters the like of Russo's. People in small towns with small ideas, small ambitions, just getting through, yet immensely likeable. These folks do not need to climb mountains to be important.

A book reviewer once noted that Russo is a great guy to have a beer with, he is relaxed and full of great repartee, and that one would quickly forget what a great writer he is. I think it's this aspect of the writer that permeates his novels, makes his characters vivid, funny, real. It's hard to let go of them.

Sunday, February 15, 2009

Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, by Barbara Kingsolver et al

Barbara Kingsolver is not a bad sort. I have enjoyed her novels in large part because of the connections the characters have with the land. And in this nonfiction work she offers useful information and a point of view that, for the most part, I share. Yet I had trouble getting through the book. It lived with me literally for months because I would pick it up, read a page or two, put it down again and reach for another book. I have no idea how many dozens (literally) of books I read at the same time.

The book is all about the Kingsolver-Hopp family going local. The four of them upped and left their western home for their farm in the country, specifically in Virginia, to spend a year being “locavores” - eating local food, most of it grown by themselves. It was an industrious effort. Nobody can accuse this family of being lazy. Yet by their own account it was not only rewarding financially, gastronomically and nutritionally, but it was fun.

Kingsolver offers us tidbits about dozens of kinds of vegetables and fruits, fiction and fact, and serves it up with more than a soupcon of self-deprecating humor. She also brings us into the land of harvesting animals, which is primarily where we part company. I learned a great deal about pumpkins, tomatoes, basil, canning, freezing, drying, and more, and I am determined to make a few changes based on what I learned. I also read bits about world hunger, the hidden costs of transporting foods, the meaning of fair trade, the expansion of farmers’ markets in this country, mostly written by Hopp. Virtually all of these global bits I already knew, but I had not considered one aspect of choosing what to import: how much water is used to produce it. Similarly the intertwined notes by Camille Kingsolver, which mainly offered the perspective of a young aware woman.

Some readers have called this family “rich white folks playing at farming” and it’s hard to deny that this is the case. They were not farming for a living, and they had other occupations. Kingsolver herself had to retreat to the computer to make notes about everything that was going on in her farming world in preparation for this book. It is quite fashionable to write about trying this or trying that for 30 days or 60 or for a year. I have been trying to think of what hook I could get hold of so I can do the same thing, frankly. To her credit, I do not think she was aware of the trendiness of this occupation. When the year was over she discovered that while the family was blissfully pulling weeds and tending turkey hens, many others were embarking on “locavore months”, for example.

I think, though, that Kingsolver offers a reasonable response to this type complaint. She kept detailed records of costs and was therefore able to prove that living off the land is indeed less expensive - assuming you have access to the land - than living from the grocery store. As for how much land, you might be surprised at how little is really required. She was easily able to make the case that eating organically is better for your health as well as the planet. More importantly, she makes a good point that you do not have to have your own farm to eat locally - at least in most of the populated parts of this country. There are farmers’ markets most of us can get to, the various public assistance programs, like WIC (women, infants, children) can be used at farmers’ markets, and we can make better use of what is nearby. Some people can grow some of their own vegetables in pots in a patio, if that’s all there is available. It isn’t impossible for most of us to live more locally than we do and enjoy it more.

Enjoying it more is only part of the point, of course. Kingsolver is not a fan of factory farming of animals or conventional farming of vegetables and fruit. She asks that we look at where our food is grown, if the people who grow it are compensated adequately and if harmful chemicals are used in its production. In the case of animals she tells us that when her family had the choice of CAFO (confined animal ) meat or no meat they chose to go vegetarian, as much because of the treatment of the animals as for the unhealthy nature of the meat itself. Again and again she drills into the reader the reasons we should think hard about our food sources.

I couldn’t agree more that current agricultural practices in this country leave in their wake clouds of noxious pesticides, damaged soil, polluted water and air, and ultimately inferior products in taste and nutritional value. The Omnivore’s Dilemma made me aware too that the practice of growing corn and soybeans results in fields lying fallow for months, adding to the waste and contributing to the loss of topsoil. The practice of trekking food across the country or even across the world adds to the environmental cost of the food and leaves us to wonder who raised and harvested that food and what costs do they pay to bring us cheap food, in addition to the questions about the food itself.

In other words, for the most part Kingsolver is preaching to a member of the choir here. I seek out organic produce at local farmers’ markets, I cook most of my meals myself, I buy fair-trade products from other countries (when local alternatives are not available). I am aware of the costs of eating Big Ag. I am not sure how this book affects those who have not been giving these concerns much thought - I do hope the effect is mainly positive. There is an overarching preachiness beneath the veneer of humor that may well turn people off, but based on the largely positive reviews I suspect most are not turned off by that tone.

My main concern with the book is the way Kingsolver discusses the animals. And my complaint is that she does not give this matter the kind of dedicated study that she gives to the vegetable sections. She short-changes the subject in favor of promoting her own prejudices.

Kingsolver argues on behalf of what has come to be known as “happy meat”. Animals raised in a pleasant environment and killed in a way that inflicts as little pain as possible, mentally and psychically (yes, I said psychically). I can’t argue that the home-grown concept is not better than factory farming, for the animals as well as the people. What I can, and do argue, is that all of the reasons Kingsolver trots out to make her case in favor of eating meat at all are weak and fall to the ground under the slightest scrutiny. As this review is long enough already I will refrain from repeating my point-by-point argument on this subject, but you can read it on this blog.

I give credit to Kingsolver for her resolve to let her turkeys mate and reproduce naturally. She resisted the incubators and the artificial insemination, learning in the process that nobody, virtually nobody, in farming today actually lets the turkeys mate naturally. She wasn’t at all sure the breed she had would succeed at it. What interested me was that she made the claim that her turkeys, being older than a few months, were among the oldest in this country. She also hunted for information on mating in agricultural books of the 1950s. I wondered about the wild turkeys. I can see scores of these wonderful birds a short distance from where I live and I am betting that 1) they know how to mate and 2) they live long, happy lives in the wild. Kingsolver’s deliberate ignorance of the wild versions of the animals she breeds raised questions to me. Admittedly, a turkey bred for factory farms and 4H clubs, bred for artificial insemination, may not be terrific at mating, but even the poorest mom is likely to have derived its technique from the same source as its wild cousins.

I recommend this book to those who can stomach the offhand cruelty inherent in this family’s use of animals - which is most of this country (but not all countries). I have come away with a few new ideas I intend to implement: I will take up drying fruits and veggies, I will consider the implications of water use in food I buy that is not local, I will do more breadmaking myself, I will even consider canning. I am not gifted in the growing department so I will not commit to growing my food for a year or even a month.

I will reiterate my animal complaint: many people share Kingsolver’s attitude toward animals. I am not accusing them of anything - I was one of them for over half of my life. What disturbs me in Kingsolver is that she did the research and should know better. Or rather, that she thinks she did the research but she didn’t, really. She misrepresents vegans, cows, chickens, and meat production in general, primarily because of her own built-in prejudice.

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

No One Heard Her Scream, by Jordan Dane

I should know better. Or maybe not. I found this book on the Publisher's Weekly notable books list for 2008. It was listed under "mass market". Mass market paperbacks do not have to be bad, I can certainly attest. In this case, though, I should have looked more closely before ordering the book from a fellow paperbackswap member.

I did not realize it was in the category of "romantic suspense", a slight improvement over straight "romantic". It's a category I don't particularly like but that I occasionally read, mainly because somebody gave me the book.

The two main characters are Rebecca ("Becca", of course) and Diego, both thirty-something or below, both coping with issues of trust, both strong and highly attractive blah blah blah...in other words, the usual characters in romantic suspense novels.

Becca is a detective in the San Antonio police department, while Diego's position is a bit more shady, man on the inside of a powerful empire led by a wealthy fifty-something man with unsavory predilections.

Becca is still trying to cope with the disappearance and apparent murder of her younger, teenage sister when she takes on an arson case that results in the discovery of a body, dead seven years. The body is of another young woman who disappeared, and the two cases appear to be connected.

From here we get romance, danger, really bad people with no redeeming qualities (not for Jordan Dane a complex antagonist), and fairly sketchy policework. Dane knows some things about police and fire procedure but not enough. Ask me about the blood spatter in the hotel room where Becca's sister was held...no, don't ask because I'm likely to forget this book within a few days.

I recommend this book to people waiting in line, people stuck on airplanes, people trying to get through the time. Or LifeTime movie producers.

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

The Atheist's Way - advance notice

There is a new book on atheism that looks excellent (I have read some of it). The book is called The Atheist’s Way: Living Well Without Gods and it’s written by Eric Maisel, known for his many books in the creativity field. I have read a couple of his other books and find his approach refreshing and straightforward.

David Mills, author of Atheist Universe, endorsed The Atheist’s Way this way: “I find Maisel's writings more witty than Hitchens, more polished and articulate than Harris, and more informative and entertaining than Dawkins. A 5-star read from cover to cover!” John Allen Paulos, author of Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don’t Add Up, wrote: “How do you bravely face the world as it is and create meaning for yourself without the crutch of a divine benefactor? The Atheist’s Way is a wonderful resource for your quest.” The Atheist’s Way has gotten many more endorsements like these and I'll be reading it myself soon.

Here is the link to the book on Amazon.

Monday, February 2, 2009

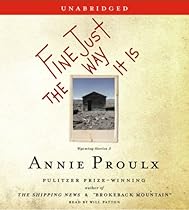

Fine Just The Way It Is, by Annie Proulx

I listened to these stories in my car, on my CD player. I think the impression a book has can vary significantly depending on how it is "read", and in this case the audio version may not have been my best choice.

Fine Just the Way It Is is a set of short stories, specifically Wyoming Stories, as its subtitle says. The stories take place in the frontier days, in the present time, and in between. They vary in specific location, in the length of the tale and in the characters. But they are all about Wyoming, as if no matter who the human character is he or she cannot shake the indelible control of Wyoming on its soul. Oh, and I don't use that term "soul" lightly. Three of the stories feature the devil him- or herself.

It's possible that the actors on Selected Shorts have spoiled me for the usual professional readers of audio books. I love to listen to Selected Shorts on public radio, to how these veteran actors read fascinating stories, bringing every one to life. During one visit to New York City I could hardly contain my excitement the night I made my way to Symphony Space to watch the actors live, and I know I would go there regularly if I lived in Manhattan.

The readers of audio books are good readers, highly qualified, yet often for me there is no good fit between them and the material - or perhaps I am simply prejudiced. I found it difficult in the present case to get comfortable with the accent and style of speaking of Will Patton. Patton was chosen, I am sure, because these stories take place in Wyoming, and he has a decidedly western accent. Beyond the accent, he places emphasis where it might be natural for a westerner. He immerses himself into these lives and it shows and yet my prejudice, from wherever it comes, against that type voice, made it difficult at all times to enjoy the stories.

Nevertheless some of these stories stood out for me. They nearly stopped me in my tracks. There is a story here of a sagebrush that takes the place, for one woman, of a child, after she has lost so many of her own human children. The sage is of such a shape that it reaches its "arms" to the sky and it is so well treated that it reaches an astonishing size. It becomes a legend in its territory. It even becomes the subject of mysterious disappearances.

Another story, near the end, is of a man and woman who get into a fight, escalating until neither can back down. The man leaves, the woman heads out the next day for a long hike, one she had intended to do with the man. She hikes past a sign that says "trail closed" and continues on, knowing she is likely to be on her own the entire way, yet keeping in mind that her former lover might see the signs and come after her. When she makes a mistake and gets caught in some rocks we get to know how each day, each hour, each minute feels for her. And how her mind goes back to that fight.

There are several long stories here, each of which I wanted to be a book in itself. The first one left me long before I was ready to go. In fact, when I realized I was listening to a batch of short stories and not one long one I initially felt cheated, because I wanted so much for that first one to continue. Would I have the same impression if I simply came to the last paragraph of a printed page? I am not sure. Perhaps in some ways audio does have an advantage (in addition to being able to occupy my mind while I travel).

These are earthy, real, unwincing stories of the west, spanning several generations. People live and die and have hard lives and we are treated to details you almost had to be there to know. Better than any history book, this set brings the west, the real west, truly alive. The details are inscribed in the faces we imagine, in the actions the characters take, in the sense of relentless fate that seems to weigh everything down. Overall, the stories feel uncomfortably real while at the same time are frequently relieved by what may be called a kind of Wyoming humor.

Sunday, January 25, 2009

Redemption, by Nathan J. Winograd

The primary message of this book is that animal shelters and humane organizations in the U.S. have lost their way. They have become killers of animals. The author takes an approach to the killing that I had never considered, that the shelters themselves are responsible for the killing, not the general public.

Winograd indicts the leaders of several major animal protection societies, including those that have never maintained shelters of their own, because these societies set standards and make pronouncements that support the killing. The reasons these leaders have not embraced “no-kill” are varied but do not stand up to scrutiny. Over the years leaders of shelters and humane organizations have resisted change to the status quo to protect the profits of veterinarians and breeders, because they don’t want to accept responsibility for their previous wrongheadedness, because they “have always done it this way”, because they simply don’t believe true no-kill is possible. Along the way they have forgotten why they were formed - for the protection of animals.

Early in the book he notes that the head of the SPCA in San Mateo, CA went public with the killing of animals. She chose to show the killing on television. To many, including the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) this was a courageous act. I happen to agree with this position in one respect: I believe that whenever our society condones the killing of people or other animals such killing should be in our face. We should know about it, no mistake. When such acts are hidden from the public people can forget it happens and convince themselves they have nothing to do with it. A friend of mine, for example, tells herself that the meat she eats comes from cows who died of old age. Such fabrications may make people feel better but they certainly do not advance any animal cause.

So I believe when animal shelters kill they should do so openly so that we can see our failure. I have been persuaded, however, by Winograd, that the failure is not ours alone. Winograd's objection to the publicized killings is that it appeared to condone the killing, to suggest that it is inevitable, and that the citizens, not the shelter, are ultimately responsible.

I honestly believe that the intent of the shelter leaders who performed these executions live was to raise awareness, in the hope that the actions would bring about behavioral change in the public. The error in their ways was in ignoring the part the shelters themselves play. Blaming us instead. By doing so they not only attacked the very people who would be their most likely supporters, financially and otherwise, but they managed to give some of us a sense of guilt that it is impossible to overcome alone. I have lived for years with the sense that I have not done enough to save the animals in shelters, yet I have believed that only a change in attitude by the public could possibly make a difference. I did not see a way that I could bring about that change, except on an individual level, and that never seems to be enough.

Winograd says that the shelters have been blaming the citizens for what they consider to be the overpopulation of companion animals and what they consider the necessary killing of many healthy animals while in fact the shelters themselves deserve the blame. My personal position is that the killing is a shared responsibility. However, the examples of a few committed shelters make it clear that shelters can end the killing without needing to rely on some vague time in the future when "the public" becomes "more responsible". Shelters can end it right now. Even in parts of the country where the public is supposedly too ignorant or poor to get their animals neutered or to provide veterinary care to them.

The further I got into the book the more I came around to Winograd's position. And the more I came to the sickening conclusion that the organizations that are supposed to be protecting our animals are not only needlessly killing them, but are at the same time attacking those shelters that have indeed achieved a real no-kill status. It is this resistance that forms the core of the message, because the means are available to make this a no-kill country. Now. Virtually overnight.

Paramount to understanding why this can be done is knowing that in fact that pet overpopulation is a myth. This simple fact, illustrated in this book, knocks all other arguments on their heads.

Winograd's method, which he calls the No-Kill Equation, includes several actions that any shelter can take:

* Neuter all animals that enter the shelter except those that are incurably and painfully ill and must be euthanized for that reason.

* Support and even operate Trap-Neuter-Release programs for feral cats in the community.

* Use volunteers to socialize and foster animals to make them more readily adoptable and to create additional space in the shelter.

* Provide medical care and isolation as needed for sick animals

* Use the media to bring the animals and their needs to the public

* Expand shelter hours and offer off-site adoptions to meet the needs of the public

* Allow animal protection groups to take healthy animals for adoption at their shelters or off-site adoptions

* Get rid of employees who can’t get with the program and bring in those who can.

Winograd currently accepts the killing of dogs that are considered irretrievably vicious, because to date there are not enough sanctuaries for these dogs. I have difficulty with this position because these are innocent dogs who deserve to live. They may not be suitable companion animals but there are not a lot of them (by his own calculations) and I suspect there are enough sanctuaries who can accommodate them. Best Friends Animal Sanctuary always finds a way to keep animals alive, including those with behavior problems. This one issue is a type of quibble, though, in the face of the astonishing success Winograd outlines here.

In the cases Winograd outlines in this book, media attention on the activities of true no-kill shelters (those that are not selective in the animals they take in) quickly brought in the money needed to undertake all of the above actions, and eventually the aggressive actions reduced the number of animals brought into the shelters. It's a win-win all around. But it only works, Winograd reminds us again and again, if the shelter is absolutely committed. His three-step program:

* Stop the killing

* Stop the killing

* Stop the killing

Unless shelter directors and staff are fully committed to stopping the killing it will go on. It is unfortunate that at this time it takes special directors to achieve no-kill status, but even this situation can and likely will change. Winograd sees a change in the public perception of animal shelters based on greater visibility, and accordingly the public will no longer accept the standard operating procedures that are so common today.

I don't feel as hopeless now. I know what tools can be used at the shelters and I know I can demand that these tools be used.

Every shelter should have this book. Every governing board that regulates these shelters should read this book. And every humane society leadership should read this book. And honestly pay attention to it.

book rating: 10 out of 10