“I have a glandular problem,” sneers the unattractive, heavy, odoriferous mother of a serial killer in the television series Bones.

Here you have a rather typical, if overdone, version of a fat person as shown on television or in the movies. If she's fat there is something fundamentally wrong with her. She's unlikeable, she smells, she blames a condition or others for her fat. She's morally bankrupt.

A more sympathetic version is Bridget Jones as played by Renee Zellweger in the movie

Bridget Jones's Diary. She's a little “thick”. I don't think “heavy” or “fat” apply here. In fact, the actress gained weight to play the part but she is still an average weight in this movie – just fat in comparison to other movie actresses. But the story here is a cinderella one in which the glam guy goes for her even though she's fat. Which she isn't, really, but let's play along.

Fat people don't get the title roles except in unusual circumstances, like

Cracker (British version, with Robbie Coltrane, incredible actor) and

Murder One (another terrific show in which the lead, the charismatic Daniel Benzali, is a mite chubby (and bald)). Fat people don't get asked on dates, except by so-called BBW-lovers. Fat people don't get promoted. And fat people are the butt of major jokes, some of which are full-length movies.

The cultural disgust with large persons is grounded in myths about what large people represent. The disgust isn't because thin people are concerned that fat people are unhealthy. However, the medical community has jumped wholeheartedly on that bandwagon. A day doesn't go by when we don't see an article somewhere that points out the “fact” that because they are fatter, this generation is going to die sooner than their parents.

In the Obesity Myth, Paul Campos sets the record straight. And does so with a passion often absent from medical nonfiction, along with a healthy dose of humor.

Early on, though, he makes a note in passing that he was fat and now he's not, and he'll explain later. He makes the comment to underline the fact that he knows what it is to be fat. I appreciate that but at the same time I found myself wondering as I made my way through, just what will he reveal about himself later? Is he going to reveal some sort of super diet after all??

Fortunately, he does redeem himself later, through his honesty and insight into himself. He can write passionately about the pain and frustration with the diet industry because he is, as much as any of the rest of us who obsess about weight, a victim. Even knowing the facts does not change what we want for ourselves. It turns out that this personal section, for me, is the best part of the book, because it brings it home.

But first, what are those facts? Campos tells us more than once (and a good thing, too; some facts bear repeating):

* It is healthier (from a mortality standpoint) to be 75 pounds overweight than 5 pounds underweight, if you are moderately active. Moderately active translates to four or five brisk 1/2-hour walks per week. I have read elsewhere that the difference is two hours of moderate exercise per week, which is comparable.

* Two persons of the same weight and height can respond to the same food in entirely different ways. In one experiment, 16 persons were “overfed” by 1,000 calories per day, six days a week, for eight weeks. Their activities and food intake were strictly controlled. Their caloric burning capacity was measured. The experimenters discovered a huge range in energy expenditure: from 0 calories to 692. In other words, some subjects burned 692 more calories per day than others, while engaging in similar physical activities and eating the same amount and type of food.

* Dieting is the problem, not the solution. Persons who go on calorie-restricted diets lose weight, then regain it, and gain more. The more often they diet the more they ultimately gain. There are few exceptions. (The exceptions are interesting and a little scary; read more about them in this book.) Although many feel virtuous when dieting, feeling hungry is not good for your body.

* There is no difference in mortality between persons of average weight and persons of higher weight in terms of overall health, when you control for levels of activity and type of food they eat. Shockingly, even the standard claims that fat persons are more likely to develop heart disease and type 2 diabetes are not supported by the facts. The association between fat and heart disease actually is a connection between those who have gone on calorie-restricted diets and heart problems. Those at the same weights who never dieted do not exhibit these heart problems.

Weight itself is not a problem for mortality. If there is no “healthy weight”, then (thin persons can be unhealthier than fat ones, for instance), there can be no “overweight”. The only time weight is a factor is when it is so extreme that it makes the person essentially immobile.

Why then do so many of us believe fat people are unhealthy? We can all point to relatives who lived long and satisfied lives in spite of being large. We all know many thin persons who are unhealthy. It is true that being fat usually limits our ability to move as well as we'd like, take part in some activities we might otherwise enjoy. Why – admit it – are you thinking right now that I am making excuses for myself??

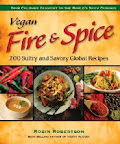

I struggle with that last. As a vegan I know that I am seen as an example of a group of people who eat differently than most other Americans. I feel an obligation to be seen as healthy and well, and I know that to many I do not appear to be, mainly because I'm fat.

Campos phrases it differently. He answers the charge, “You are giving people permission to be fat” with the countercharge: “As opposed to what: not giving people permission to be fat?” and then points out just how well that approach has worked in the last 100 years. It is just that approach that has taken us here, ironically. Stigmatize, attack, accuse people of being lazy, immoral, dirty, ignorant, lacking in willpower, and what happens? Eventually they believe it. In spite of evidence to the contrary, often evidence anyone can see. And it is incredibly difficult to change the way you think about yourself when you've had so much help over the years.

There are no absolute answers here, no roadmap to a brighter future. The forces that have brought us to this place are larger than we are. Campos does help us see beyond “common knowledge” and suggests that we replace myth with reality. We need more books of this caliber on this subject.

The story, of Liesel, a young German girl during world war II, is told by Death. And Death has an odd way of speaking. It’s a combination of sly, often grim, humor in the storytelling, and interjections of bold-face explanations, sometimes translations of words, sometimes descriptions of a character’s thinking process. For example,

The story, of Liesel, a young German girl during world war II, is told by Death. And Death has an odd way of speaking. It’s a combination of sly, often grim, humor in the storytelling, and interjections of bold-face explanations, sometimes translations of words, sometimes descriptions of a character’s thinking process. For example,